Broomstraw Brooms

I call it broomstraw. Others broomsedge. Whatever you call it, it doesn’t kill my memories of my grandmother’s homemade brooms. About a yardstick long, they stood in corners throughout the house. That made them handy. They were simple. They were effective. They were attractive in a rustic way, golden shocks of broomstraw bunched tightly in place by black inner tube. And did I tell you they cost not a dime?

My grandmother lived a farm life and farm life taught her you didn’t have to buy essential items. You made them. Brooms? All she needed was a field of straw and a few lengths of inner tube. She didn’t use twine. That would loosen and you’d have a mess on your hands. She preferred inner tube. There was a time that when an old tire blew out, wore out, or just slap dab failed, its inner tube was worth salvaging. Those hardy people who survived the Great Depression found creative uses for many things. “Keep something seven years and you’ll find a new use for it” went the old saying.

Three books back and a good many years ago, photographer Robert Clark and I visited the Broom Lady in Boykin Mill, South Carolina. She made stick brooms from straw out of Laredo, Texas. Blond and stiff as hog bristles, her brooms could sweep the sea back. She dyed the straw to create a stick broom that rivaled a rainbow. She had a waiting list a mile long for her artsy brooms. I wonder, though. Did she ever make a broomstraw broom?

Nowadays folks buy stick brooms, high-dollar vacuums, and those push-button Swiffer things. In 2023 people spent $990 million on floor vacuums. Broomstraw is free.

I photographed a field of broomstraw up in North Carolina. It had enough straw to make hundreds of brooms. My grandmother would have turned that field into a broomstraw factory. Tell me readers; do folks still make brooms from broomstraw? I say no, though I hope someone does. It’s uplifting to think that ordinary people still make simple brooms from broomsedge.

My grandmother was tall. I see her now walking through a field of broomstraw, leaning over to gather straw. Back home she cut the ends clean and patted them into place, much as a smoker will tap his cigarette a few times. She’d firm up a good hand’s worth of straw, wrap a length of inner tube around the truncated ends, squeezing them tight as nails. Several other lengths spaced just so solidified the broom. It had no stick. The tightly squeezed straw was the handle. With the business end ready for service, she swept up life’s detritus as quietly as falling ash.

My grandmother lived simply, as people once did. Those days are gone. And handmade brooms are gone except perhaps in some history village where one stands by an old oak bucket, but fields of broomsedge still grow and when I see one, I harvest memories.

Times change and what used to be a field of brooms in waiting is now just a nuisance to the farmer. Still, it makes for a beautiful setting, something that artist, Andrew Wyeth, might have painted.

Here’s to my grandmother for making good use of natural things. When we fished the farm ponds and gave out of worms, she’d turn over a few cow piles (sun-baked cakes, as Mom referred to them), and we had a new supply of bait. She churned her own butter too, golden mounds of glistening butter, but that’s a story for another day.

When the Border Boys Were Young

Before the photos, Robert Clark had been photographing architecture for ten years. I had been writing scripts for documentaries. Much earlier, during a teaching stint, I submitted a paper to an academic journal. That earned me an invitation to speak in Kansas City, Missouri. I turned the offer down. Grinding out dry treatises was not, and would not be, my cup of tea.

In short, I left full-time teaching and found my calling. Back when we were young, Robert’s path and mine crossed at a natural resources agency. I wrote the aforementioned scripts, and Robert photographed wildlife. Later I joined the agency’s magazine staff where editors and designers combined words and images to craft features about man’s relationship with nature. After three years of staff meetings but not one chance to work together, Robert suggested we take a day off and hit a back road.

“We’ll find a story we both like,” he said.

That we did. “Tenant Homes, A Testament To Hard Times” chronicled plain folk’s hardscrabble life. In one shack, an elderly lady had scraped by selling lye soap and “flowers” cut from pink and mint green Styrofoam egg cartons. She had died two weeks earlier and her unfinished work lay among rat pellets. Her story lives on, here even.

Several months after the publication of “Tenant Homes,” Warren Slesinger, acquisition editor with the University of South Carolina Press called. “I read the story you and Robert did, and if you have more stories like that, I have a book contract for you.”

We did, and he did.

That was thirty-five years and six books ago, our latest release being Carolina Bays: Wild, Mysterious, and Majestic Landforms (Jan. 2020). Over seven years we logged 10,000 miles across North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, observing and photographing Carolina bays. Of the book these words were written. “There is a strange beauty at the heart of every mystery, and the mystery of the Carolina Bays is an enigma that is lushly, uniquely beautiful. How did these odd features come to be formed in the landscape in the first place, with their uniform shapes and matching elliptical orientations scattered across the Carolinas? There are many hypotheses but no definitive answers.”

Our latest work will be out early in 2025. For now, it’s a secret.

Today we cover back roads, dying farms, abandoned churches, shuttered country stores, nature, of course, and winsome places like gristmills, kudzu-covered trucks, feed and seed stores, covered bridges, and forgotten bridges. Like me, Robert prefers the road less traveled, and it’s there he captures images you cannot forget.

“There’s a reason you’ve seen Robert Clark’s photographs in the pages of National Geographic books, a reason you remember them long after you’ve turned the page. Clark’s work captures more than the look of a place; it communicates the mood.” —Chicago Tribune

“Tom Poland is an inquisitive man who keeps an eye out for extravagant chunks of nature, disappearing cultures, and people who are salt of the earth. He has ridden those so-called back roads for years chewing foods, sipping drinks, absorbing stories and documenting his finds. Change is what Poland touches upon frequently.” —Wayne Ford of the Athens Banner Herald

What we do is not work, but as Robert said, “It requires discipline.” Our bosses are weather, the clock, and deadlines. Robert works at sunrise and sunset to capture the magical light, and the nine hours a day I put in isn’t work, not when you love what you do.

It’s been half a century since I picked up the pen; half a century since Robert slung a camera around his neck, an odd thing. Robert grew up dreaming of being a writer, and I grew up dreaming of being a photographer. In a reversal of dreams, I became a writer and Robert became a photographer.

Today, we both write and photograph, together and apart. Think of us as the Border Boys. Robert’s from Charlotte, and I’m from Lincolnton, Georgia. Two outsiders on the inside now for fifty years.

Running With Ghosts

I dreamed I was in a football game again. Then I awoke. Such disappointment. Other than playing in a game again, the next best thing would be watching my old game films, an impossibility. Properly stored 16mm film can last 70 years, but those old 16 mm projectors surely saw the landfill long ago. There was just no way to see them.

I contacted Red Devil curator, Johnny Walton. “Did any of my old game films survive?” Johnny sent me a message. “You can see game films from your high school years online.” Through the miracle of digital technology a few games were there—Wadley, Sparta, Louisville, Putnam County, Mount de Sales, and Greensboro. In flickering light my teammates and I took the field again.

We went a pedestrian 7-3. Unlike the teams of the early 1960s we left no legacy. Not one trophy. Not one scholarship awarded. I better recall my 1964 and 1965 teams. Over two seasons we went 15-3-2 and shut out 10 opponents. Even so, we were a letdown. The 1963 team’s Great Red Wall shut out ten of twelve opponents in one season and won the state championship. (The six teams that followed my ’66 team went a combined 25-29-4. In 1973 a Larry Campbell-coached team went 8-1-1, and the greatest run in Red Devil history had begun.)

Those old game films? They had no sound. Some online versions feature soundtracks. In one, the Beach Boys’ “Surfer Girl” plays. Seems I hear a Jan and Dean track, the California sound the Beatles killed off. The camera work is primitive. The camera hovers over the line of scrimmage, perhaps a limitation of the lens. Anyone in the secondary might as well not exist. Even so, the images bring back memories. You remember, that is you think you remember, the plays. You feel the hits once again. Hephzibah 1966. We’re wearing red jerseys though playing away. Our helmets look out of date because they are. We won 18 to 6.

I watched the old films in a mild state of time travel shock. Like some scene from a silent film of the early 1900s, No. 13 runs with ghosts in out-of-focus scenes that unfold in slow, dream-like images. I make a run, 20 yards, against Putnam County only to fumble when hit up high. Other games; other players. Sammy Evans, No. 21, drops back, breaks and runs for five yards. Dwaine Biggerstaff, No. 40, takes the ball up the gut for a score. No. 70, Leon Cox, takes measured strides. His approach seems stiff as he kicks the ball. The soccer boys’ sidewinding style had yet to arrive. Once it did, the straight-ahead kick was done. And after a drubbing from Warrenton, 47-0, we were done, our playing days over.

—

When I tell folks I’m from Lincolnton, Georgia, some ask a question.

“They have good teams down there. Did you play?”

“I did,” I say. “My senior team was average. No athletes.” It was true. As proof, too few players went out for track team in the spring of ’67. No team, a sore spot with me still. I had gone to state the year before in the 440-yard dash. There would be no chance to go back. No chance to do better.

A lot of fellows I meet tell me they never played football. “Why not,” I ask. “Too rough a sport. My mother didn’t want me to get hurt. Our team was terrible.” I see, I say, and what I see are men who missed out on a great experience. You only go around once. Give it all you have. For those who do, the reward is great memories, win, lose, or draw.

Sixteen seniors played on the 1966 team. Six are gone now to heart attacks, strokes, a car wreck, and sheer bad luck. Some evenings I return to those grainy, flickering, slow-motion films. It’s like watching ghosts by candlelight on a field that has become a cemetery where dead men rise from the ground to play ball once again, but no track. Their running days—not mine—were over.

Time, The Silent Thief

Growing up I could hear the tick of my church’s old Regulator wall clock. I can’t hear it today, but my hearing’s good. All that keeping of time must have silenced the Regulator’s tick and that’s appropriate. Time is fleeting in a silent unnoticed way.

I got caught up in the race and somewhere between 1996 and 2015 time stole not nineteen years but my life. One day it struck me that my daughters were grown. One day it hit me how many people I knew were dead. One day I realized others had gone into shells that swallowed their lives entire. I looked back on the jobs I’d held and how important they were but in the end they amounted to nothing. We waste a lot of time worrying when we should be remembering.

I look a lot now at what was and I do what many will think is a strange thing. On a regular basis I drive up Georgia Highway 79 and park and lean on a steel gate and stare at mom’s old homeplace. All a stranger will see is grass, trees, and an old store converted to a hunting camp. Not me. I see family. Meals. Games with cousins. Cold winter nights around a wood stove. Sinking deep into a cold feather bed. Drawing a bucket of water up from a well. A smokehouse. Penny candy. Outhouse. Crab apples. Bamboo peashooters. Arrowheads, Indian pennies, and more. Come with me one day and I’ll tell you a whole lot more about all I see in that patch of grass and weeds.

Oh. Well, that’s okay. I knew you wouldn’t have the time to join me.

Time. The New Oxford American Dictionary defines time as the “indefinite continued progress of existence and events in the past, present, and future regarded as a whole.” I define it as the stuff memories are made from. However you define it, time always seems to be in short supply but that doesn’t stop people from spending a lot of time writing about time.

In his epic poem, “Looking For The Buckhead Boys,” James Dickey gives us these lines after learning many years later that his old high school teammates are dead from heart attacks, war, and one’s paralyzed, one’s in jail, and others maligned in other ways by the clock. He remembers they lived and writes there are “sunlit pictures in the Book of the Dead to prove it: the 1939 North Fulton High School Annual. O the Book/Of the Dead, and the dead, bright sun on the page/Where the team stands ready to explode/In all directions with Time.”

Explode in all directions is right. People move never to be heard from again. Where, I wonder, is Benjamin Bradford? Where is Jean Gassaway? Where did Tommy Kennedy go? I know where Eddie, Mike, Dawkins, Janis, Sammy, and Peggy are. Gone. Gone forever. Time is fleeting and ruthless.

In “Time,” Pink Floyd gives us this line: “Ticking away the moments that make up a dull day” and this one, “Every year is getting shorter, never seem to find the time.” It’s true. A dull day seems far longer than a day spent adventuring. And it’s true that each year burns up faster than the one before.

Can you hear time? Yes, a newborn baby cries. A young boy’s voice begins to change. Brakes lock and tires squeal just before that awful sound. A siren screams down a highway. A bell tolls in the distance.

Can you see time? Sure. You see it as a tombstone. An abandoned home. A wooden cross in a highway curve. A clear-cut forest. A hearse. A wheelchair ramp.

I see it as an old chair no one sits in anymore. Covered in rust with a bent leg it nonetheless possesses beauty and it’s a fine place to set a favorite book, dried flowers, and hourglass to signify the passing of time. Seems an old soap opera used to open with the saying, “Like sands through an hourglass, these are the days of our lives.” How true.

Time. It’s the most important thing we spend. Don’t waste it.

Coming Full Circle

I felt like I’d been tied to the whipping post. I was as low as the proverbial snake’s belly. May 30 a tornado destroyed my Athens, Georgia, home. My marriage was floundering, and I found myself with nothing but the clothes on my back and a banged-up stereo system. Thank heavens that sound system survived the tornado. Music kept me afloat the summer of 1973.

Four years earlier, Capricorn Records had released “The Allman Brothers Band.” It released “Brothers and Sisters” August 1973. That record, the band’s fourth studio album and the 1969 record lifted my spirits during the difficult summer of 1973. Living in the musty basement of a brick house along Highway 78 I wore both albums out. The Beatles had broken up and I needed new music heroes. I found them in the Allman Brothers, and they hailed from Macon, Georgia, less than two hours away.

Driving to Macon was out of the question. I worked full time as a ticket agent at the bus station, took a full load of courses, and taught classes as a grad assistant. I sensed, though, that someday somehow I would see where the boys made that marvelous music. In the years to come I drove to Macon seven times but I could never work Capricorn Records into my schedule. Trips to interview an attorney for a book, to speak to the Georgia Huguenot Society, and a drive to see Georgia’s folk drama, Swamp Gravy, stage my play took me through Macon but time was short as always.

And so my Allman Brothers wish list languished. On it were four items: Rose Hill Cemetery, Capricorn Records, the Big House (Allman Brothers’ residence/museum), and perchance someday meet legendary musician Chuck Leavell who lived south of Macon. The chance to meet him was coming in a surprising way.

Fall of 1973 my department chair called me into her office. “I’m sending you to Columbia, South Carolina, to teach for six months at a small college.” Six months led to many years. That difficult summer of 1973 was to be my last living in Georgia, but the move to Columbia opened doors. In 2018 I wrote features for an excellent magazine. My last assignment for the magazine was to profile Chuck Leavell. Things went well with the February 2019 interview and subsequent feature and I made several trips back to Charlane Woodlands, Chuck and wife Rose Lane’s home, to write a feature on Rose Lane.

As a result of my work, Chuck asked me to co-write his memoir. Recently he invited me to stay at his place and attend a September 6 event at Capricorn where he was to discuss a book recalling the Allman Brothers’ days when they were known as the Allman Joys.

Mercer University now operates Capricorn as Capricorn Sound Studios. I stood where the music had been laid down for all to hear. Songs filled my head as I looked at the piano Chuck had given the studio. “Jessica” came to me as clear as a bell. “Trouble No More” and “Every Hungry Woman” played in my head, as did “Dreams.” The next day I thought of “Rambling Man” as I rolled down Highway 41 in Macon. I’d come full circle since that difficult summer of 1973.

Those longhaired, rough and rowdy boys blessed us with a new genre of music, “Southern Rock,” and they had saved me when I most needed saving. Way, way back in 1973 the idea formed that someday I would make it to Macon and see where legends had risen, and I did.

Other bands added to Southern Rock, among them Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Marshall Tucker Band, and much later the Black Crows, but it’s the Allman Brothers I go back to time and time again. Trips to visit Chuck Leavell as I co-write his memoir of tree farming and rock music have given me the chance to visit Rose Hill Cemetery where Duane and Greg Allman sleep, Capricorn Sound Studios, and the Big House where the Brothers lived.

Sometimes you just have to wait and hope things will play out as you wish. My old car is long gone, my girls are grown, and my hair is silver. That music, though? It’s as good as ever, as good as it was when I played it over and over in the musty basement of a house that still stands.

My Father’s Razor

November 15 my father will have been gone twenty years. Twenty years. Seems like yesterday when he lay in a bed at MUSC in Charleston. Seems like last night we were back home changing out his pajamas during all those long hours of night sweats … from midnight to dawn.

We lost a long, hard war. I say we; he lost a war. No, we lost a war too. You’ve heard the saying, “When one family member has cancer, the whole family has cancer.” It’s true. Esophageal cancer killed him and damn near killed us too.

Dad fought an Axis of Fate whose three members were time in Hiroshima, cigarettes called Chesterfields, and vapors emanating from years of welding, all those rods melting and releasing fumes. He didn’t stand a Chinaman’s chance to put it politically incorrect. And he couldn’t speak. The surgeon removed his larynx along with his esophagus.

We did what we could for him at MUSC. At least we tried. Among the things we did was shave him. My father had a tough beard. When it became difficult to use a safety razor on him, we decided to buy him an electric razor. Seems I recall my brother-in-law, Joe, and I went to a Walmart in Charleston and bought a Norelco. It featured three floating heads for comfort. Comfort. What was that to a man experiencing hallucinations and night sweats. I don’t think it helped Dad feel more comfortable, but we’d shave him, the razor humming, and he’d turn his blue eyes to us and mouth, “thank you.”

The pamphlet the razor came with guaranteed a close cut. “Change heads every two years for best results” it advised. “Replace the blades within two years and get back to 100% performance.” It said that too.

We never replaced anything. Dad died November 15, 2003. All in all, he lingered twenty-two months after surgery, eating through a feeding tube, breathing through a stoma cut into his trachea, and trying to talk, for a while, with an electrolarynx. He sounded like a robot, like someone from a science fiction movie. He quit on that electronic voice thing. I would have too. The electrolarynx ended up in a drawer. And so did the razor.

After Dad died, my sisters told me to take the Norelco. I knew I would never use it. I brought it home to my place in South Carolina, and that’s where it ended up in a drawer. A lot of years went by. I didn’t use it. I never will. Something about plugging it up and hearing its electric buzz bothers me. Ghosts. Sadness.

I shave with a Braun electric razor and a real razor, a safety razor with three blades. It’s a two-stage process. I shave with the Braun, then lather up with soap and finish my daily task. It comes automatic to me. Some fifteen years after Dad died, after shaving one morning, God knows why, I got Dad’s razor out of that drawer. I sat on my sofa and placed the razor on my coffee table. Bathed in morning light, I stared at it. Memories aplenty came to me. Most I’d like to forget. And then, for some inexplicable reason, I removed the three-headed cover and clippings from Dad’s beard fell onto the fine-grained table. Sunlight struck them and they glistened like a scattering of salt and pepper. My breath left me. I wept. Some of his earthly remains at long last saw the light of day. He was still with me. I wept some more.

I did my best to put the clippings back in the razor where they remain to this day. I cannot bring myself to look at them again.

I don’t know why I wrote this column for a bunch of strangers. A few of you, though, you knew the man. I wrote it for him and you, but most of all, for me. I just wanted to share something. Sometimes someone we love is not gone. They’re closer than we think.

The Morning Routine

Come daybreak, my preferred time to get moving, I check on my neighbor’s flag. I check to see that his place is ok after another night of living in America, (thank you, James Brown), and to see if the wind’s about, a weather thing. Generally, all seems well, but as I move toward the kitchen storm winds gather and a US flag flies in the gusts blowing through memory.

As my mother’s health spiraled down, her morning routine became mine. I’ll spare you the details, but it included opening the blinds, getting her glasses, settling her in her favorite chair to watch the news, breakfast, and a glance out the window to see if her flags had wrapped around their staff overnight. Sometimes they had, and I’d walk down the long driveway to free Old Glory and her Georgia Bulldog flag. Sometimes a stick or rake worked. Sometimes I needed a ladder to reach the flags seemingly growing from Georgia pines. Many a morning that was part of my routine. Freeing her flags.

And then she freed herself.

Memories of Mom’s flags live on, so when driving back roads, my preferred way to get from A to B, I note the flags attached to homes, trees, and poles. Who keeps an eye on things and how does their day start? Who unwinds those flags when winds toss them about?

My years and miles of flag watching prove revealing. For one thing, I don’t see that many flags at new homes. Nor do I see them at places where hard times dwell. Money’s too tight. I see a correlation too. Old homes, old people, and tattered flags seem to go together. My guess is a sizable stack of years clears the fog, opens eyes, and allows a tad more wisdom, respect, and appreciation to enter.

When I see an old home with foot-high grass and shrubbery a tad wild and a wheelchair ramp I know someone’s flags face windless days. For now who frees the flag wrapped around their staff? What will become of old sun-blanched flags down the road?

The other day a fellow told me to drive a certain back road. I did and I hit the jackpot. That road catapulted me into the past, a land forgotten by time. Around a curve sat a homeplace that compelled me to visit it. On its front porch I spotted a flag resting in a chair. Someone had placed it there with care. Something tells me that flag will fly yet again beneath the Southern sun.

Flags. They symbolize what people feel, believe, and love. Through my windshield I see Old Glory’s red, white, and blue. I see vibrant orange Clemson flags, garnet USC flags, pale orange Tennessee flags, crimson Bama flags, and sometimes a flag from some university where football is just a game, not a religion. Once in a blue moon I see a red flag called truth.

As I wrote this column, I saw with perfect clarity just how time breaks everything. The realization that my youth and homeplace were no more filled my eyes with tears. I almost sobbed. Almost. Memories of home and family life blew into my mind, a wind laden with all that had passed. All that once was. Writing it made me feel like an orphan. Abandoned. Well, we carry on, don’t we.

Today my morning routine includes a visual check on my neighbor’s flag. That’s as close as I get to those days when my mother’s ways became mine. As close as I get to my father who served in Hiroshima and worked so hard to provide for us. As close as I get to the days that shaped me into what I would become.

I’ll go back to that flag in the chair. I’ll kneel before it and thank it for spurring me to write “The Morning Routine.” It made me remember. Made me remember what matters. Made me appreciative.

We’re Sending You To …

In the 1960s my father visited the Central State Hospital in Georgia. He may have gone to visit a relative. I recall a heated family gathering in the dining room. A relative had the family up in arms. I was just a boy but I remember my father refused to sign documents sending the relative away. Perhaps the rest outvoted him. Regardless of why he went, he saw a terrible sight at the old mental institution. He looked through a window and saw people playing with their excrement.

But something else made the place more frightening, something dark. In the 1950s, if your family so decided, they could send you to that place with the terrifying name … Milledgeville.”

—

The name wormed its way into my brain. All my life I heard of it in sinister tones of voice. I didn’t set eyes on Milledgeville until January 26, 2023. I was driving to Macon to speak to the Georgia Huguenot Society. I decided to stay in Milledgeville just so I could visit the notorious Central State Hospital. For two afternoons I explored this infamous institution. What I saw shocked me in a strange way.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions, in this case managing mental illness and the craziness that attends it. The asylum started in 1837, an era when blunt words ruled the day. Georgia lawmakers authorized a “Lunatic, Idiot, and Epileptic Asylum”—how’s that strike you, politically correct? Before you judge, be thankful you live today and not then and not near Milledgeville.

The actual opening took place in 1842. How big was it? Well, at one point it was the world’s largest mental institution. One hundred years after its opening, 200 buildings sprawled over 2,000 acres. Today, with its star magnolias and pecan orchard, columned ruins, waterless fountains, wreathes, and decaying timbers and broken windows, it evokes a campus where faculty, administrators, and students—dead all—walk around as ghosts. As evidence, a prop from Halloween, a macabre woman, hung from the second story’s balcony. A college campus that’s what it looked like and it shocked me in a strange way. Where was the football field?

Buzzards circled the place as old men gathered pecans in a grassy rectangle. The quad, if you prefer, sits near the Jones Building, down a ways from the Powell Building, the main administration-patient building designed to look like the US Capitol. And it does. Draw your own conclusion.

That sunny afternoon I heard nothing but wind, birds, and traffic driving through the grounds, but I knew howls and screams had echoed throughout some buildings. It was a place of electroshock therapy, lobotomies, and other ways to set minds right. Like putting kids in metal cages and strapping folks in straightjackets. “Be still. Let me tighten this a bit more.”

Some suffered disabilities. A lot of people ended up here that shouldn’t have. Some exhausted their family’s patience and off they went to that terrible place of just one name.

Milledgeville.

Here’s a story from an anonymous soul. “My grandfather committed suicide at Milledgeville. Back in the ’40s and ’50s, it was not difficult to get someone involuntarily committed to a mental hospital. One of my grandmother’s sisters had my grandfather committed to Milledgeville. After a few years, he hung himself. I never met him. I think I was five or six when he committed suicide. The family never talked about it. I didn’t discover the facts until I was in my 20s. I’m not sure my grandmother ever forgave her sister. I have always wondered if, with modern medicine, he would have ever had to go there.”

—

I found the cemetery where some 25,000 nameless people were buried with numbered markers. In explanation, I read this: “Some 2,000 cast-iron markers at Cedar Lane Cemetery commemorate the 25,000 patients buried on the hospital grounds. The markers, with numbers instead of names, once identified individual graves but were pulled up and tossed into the woods by unknowing prison inmates working as groundskeepers to make mowing easier.” —Doug Monroe, Atlanta Magazine

I know the place did some some good, and friendships and romances formed there but that’s hard to believe when you drive past the fan of cast-iron markers that create illusions, when you drive through iron gates with gold angels, down Cedar Lane to the bronze angel guarding the dead. Someone had placed a quarter in her right hand. Her other hand, reaching skyward, held a garland of flowers … artificial.

It was time to go. As the sun sank, I stopped at the Admissions Office where a sign proclaimed “Quality Service Provided In A Caring Way.” I daresay some families let out a sigh of relief upon parking there, but for many sad souls that office had the most feared steps in Georgia. For many, it was the end of the line.

An all-male facility … rooms with a view.

The Pull Of The Macon Music Scene

I find my mind drifting back to Macon, and then I find myself driving kudzu-bordered roads. Macon, Georgia sits in the middle of Georgia. It’s not an easy drive from Columbia, South Carolina, to Macon but I’ve made it several times.

Macon memories …. In earlier times I went to Macon to run in a state track meet, play a football game, then much later to interview an attorney, and later still to interview a man who plays music with the Rolling Stones. Something about the city keeps pulling me back, and I will be going again and again.

The first of my last three trips to Macon proved memorable. It was late on a cold January afternoon when I arrived at the Macon Marriott after a three-hour drive through back roads. I had driven past winter-sad kudzu, which mourning the passing of the growth season, fell heavily over woods and houses. Were it summer, I’d have driven through a landscape of green mounds, curves, and contours where kudzu mobbed woods like some topiary artist gone mad. Winter’s brown back roads nonetheless made a wonderful escape from colorless Interstate 20.

I checked in, took up my bags, then headed to Rose Hill Cemetery, a sprawling graveyard of hills and stones where lanes let you drive through this city of the dead. No driving for me. I walk old cemeteries and read epitaphs. Besides, something about riding through tombstones seems disrespectful.

Macon’s music scene, tied to Rose Hill as it is, doesn’t play second fiddle. It’s rich, the home to Little Richard (Richard Wayne Penniman), Otis Redding, the Allman Brothers Band, Ronnie Hammond of Atlanta Rhythm Section, Bill Berry of R.E.M., just a ways south, Chuck Leavell, the aforementioned Rolling Stone musician. And Macon was home to a legendary recording label, Phil Walden’s Capricorn Records. Music historians credit it for creating the Southern Rock genre. That makes it hallowed ground, ground zero.

Macon, music, memories, and mourning seem to go together. In Rose Hill Cemetery, hallowed ground of another kind, there’s a grave with a pentagon headstone, Elizabeth Reed’s. Born November 9, 1845, died May 3, 1935, Elizabeth arced across the sky, a silver meteor of fame, when the Allman Brothers Band recorded Dickey Betts’s instrumental composition, “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed (Napier). A storied legend attends the song, which for now I’ll leave at peace.

Up a long flight of steps I paid my respects to the musicians asleep in Rose Hill. With “Elizabeth Reed” playing in my head, I started down the long flight of steps, bright in the gloaming from an accretion of sunlight and moonlight. The moon was filtering light through pines down by the Ocmulgee. Soon the steps would trade sunlight for the light of the silvery moon. The next day I had an interview to do so I did not get to see Walden’s legendary Capricorn Records, said to have resembled a warehouse in its early days. It was there that the Marshall Tucker Band, Sea Level, Percy Sledge, Wet Willie, Delbert McClinton, and the Dixie Dregs made music, among others.

Macon magic. I read on Macon’s Music Heritage webpage that some say it’s something in the water that inspired music greats like Little Richard, the Allman Brothers Band and Otis Redding. And then I remembered when Redding died, December 10, 1967. Plane crash. It came as a shock. As did the deaths of Duane and Greg Allman and Berry Oakley. Motorcycle.

I will write here that the Ocmulgee is a kind of Styx. Souls cross the Ocmulgee and encamp for eternity in the vales of Rose Hill. The epitaph on Berry Oakley’s grave sums things up. “The road goes on forever.” Despite the sadness, I have good memories of Macon and its region and I will return and add to them. And if I have time, I’ll ramble down highway 41.

The Colors Of Childhood

I haven’t seen the old homeplace in a while. Not my homeplace, mind you, my childhood friend’s. That would be Sweetie Boy, he of the sweet temperament that spurred Granddad to thus nickname him. His Christian name is Jessie Lee Elam. Jessie Lee-Sweetie and I spent many a day adventuring on the family farm beholding the colors of childhood.

The clock spins wildly now, and I find myself back when each summer day amounted to an adventure. In fresh air beneath the Southern sun, Sweetie and I had our own Disneyworld of pastures and ponds, breams and baseball, and woods and wasps. Yes, wasps.

Come evenings, Sweetie and I would sit in the back of Granddad’s jalopy. As we clanged past yellow bitter weeds, we eyed old wrecks in the pasture with respect. It was a battlefield, as you’ll see. During the day, we caught bluegills, tried out tomato-red persimmons, and swam in blue ponds, sometimes khaki from summer rains’ silt-laden runoff.

Most mornings I awakened to the warm-oven aroma of toasted white bread drenched with chunks of melting butter. (No store-bought margarine. My grandmother churned her own butter.) Homemade strawberry jam topped all that butter and bread. Red, yellow, and white—it made for a colorful start to a wonderful day: red-varnished cane poles, red-and-white bobbers, green algae that betrayed snakes’ wanderings, glittering jelly-like clumps of frog eggs, and Granddad’s white homemade wooden boat with ever-present black moccasins beneath it.

That battlefield of wrecks and worn out vehicles? Granddad, a veteran of the Great Depression, didn’t throw things away. “Keep something seven years, and you’ll find another use for it.” He kept his old tractors, farm implements, and all manner of scrap metal in a pasture to the side of Sweetie’s home. We found another use for his wreckage. War. All that red-rusting metal gave red wasps places to build their waxy papery nests, which we clobbered with white flint rocks. Running for our life when a boiling ball of mad wasps shot out? It ranks as one of the greatest thrills of childhood. We risked pain, and we got stung.

Those mythic days meant day-bright swims in ponds; come sundown starlight rides through darkening green pastures. Evenings sparkled too. Lightning bugs glimmered along the dark rim of woods. As the sun dropped beneath the horizon, we’d sit on Sweetie’s porch and tell stories as we looked out over a yard holding truck tires painted white—flowerpots rich with fire engine red geraniums.

By daylight we played baseball in fragrant pastures where cattle lowed. We swung ax handles, batting gravel over power lines in our version of Home Run Derby. By starlight we skipped stones across fishponds smooth as glass. We listened to bullfrogs’ sing and watched fireflies light up green clumps of rushes.

Yesteryear and its insatiable appetite for change banished the places where the colors of childhood bonded a couple of young fellas. It’s all gone now.

Sweetie’s old homeplace sits empty, my grandparents’ home burned, and the years brought change like nothing we could have seen coming. A lot of friction has crackled since those days of fishponds and wasp nests, but Sweetie and I remain friends, if no longer childhood adventurists.

We remember. It was the 1950s-60s, a time when change began to arrive full force. Strife didn’t fill our young hearts; friendship did. When that roll is called up yonder and the first of us goes home, the other will carry his brother to his final resting place. We never talked about that as boys, heck we were just kids, but the deal was in the making and it began when the colors of childhood bonded us.

The Gospel. Sunday Piano Memories

The old book and instrument of wood and ivory need each other. In fact, they share what biologists call a symbiotic relationship. In my recall of days of yore, the hymnal and old piano made beautiful music. And they still do.

When boyhood held me in its tenuous grasp, church didn’t thrill me. Oh the wasps that congregated in New Hope Baptist Church’s sanctuary entertained me. I had a secret longing that a wasp would sting someone slap dab in the middle of a sermon. What might unfold? A sting never happened but magical music did, and it lives in me still.

The music moved me through its power and it came from ordinary folk. Men, women, and children, old ladies with their hair in buns, and many a bald man and daresay one or two wearing rugs joined in the chorus to make a mighty sound to the Lord. The music proved memorable and provided a rare live performance, living as I did in a bit of a cultural desert.

Gospel music. It changed lives in intended and unintended ways. Read the bios of some legendary musicians and you’ll learn that church music steered them toward their careers. Elvis loved gospel music. So did Little Richard, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, and Sam Cooke.

Gospel takes its place among Chuck Leavell’s early musical influences. Hardscrabble musician Carl Perkins grew up the son of poor sharecroppers near Tiptonville, Tennessee, and like many Southerners, gospel music caught his ear at a young age. Gregg Allman’s rendition of “I Believe I’ll Go Back Home” hints of a gospel message—“Acknowledge that I done wrong.”

We must acknowledge that gospel music constitutes a genre of American Protestant music. Rooted in the religious revivals of the 19th century, it branched off into several directions within white and black communities. Gospel and 1920’s blues and 1930’s country music provided dark rich loam for rock ‘n’ roll’s roots. Throughout the country, gospel, folk, and blues in cities such as Memphis, Chicago, New Orleans, and others contributed to rock. Early rock ’n’ roll featured a piano or saxophone as lead instrument, but legendary bluesman Robert Johnson went down to the crossroads where the devil gave him a guitar, and the guitar would rise to prominence in the late 1950s.

As the 1950s go, the piano sits prominently at my crossroads of memories. My parents, ever dutiful, took my sisters and me to church every Sunday. I can’t sing, never could, but those old songs still play in my head. I’m going out on a limb here but seems I recall “Marching to Pretoria,” but no doubt it’s “Marching To Zion,” I recall. Pretoria doesn’t ring Biblical but I remember how the congregation sang certain songs with gusto, songs such as “What A Friend We Have In Jesus” and “Bringing In The Sheaves” was one such song also. And “Blessed Assurance,” which just popped into my head.

I can’t recall the pianists who passed through church doors but I hear them playing and see them on the bench pounding the keys and swaying. The old piano put off a honky top sound, a saloon timbre, perish the thought, but I liked it. The preacher or self-appointed song director would say, “Stand and turn to page so and so,” and the pianist would bang out a few introductory notes and folks were off to the races.

All that was long ago. These days I come across inactive churches in Georgialina. Birds nest in them. The churches stand in pine thickets, at the edge of fields, and some overlook forever-forsaken parking spaces. Pews sit empty. A piano sits in each, and now and then I spy an old hymnal.

When I’m in them I take photos and remember my childhood Sundays at church. I could always count on wearing my Sunday finest, music, preaching, and piano playing. I remember and remember and remember, and then magic takes over. In an old abandoned church, tombstones just outside its windows, I close my eyes, wasps take wing, the choir stands, music comes to me, and when some player piano cranks out a honky-tonk sound, Mom and Dad stand and the congregation bursts into song and it’s the 1950s all over again.

Sam Morton

Renaissance Man, Friend, and Family Man

Thunderstorms rumbled through the Midlands April 1 around 4 a.m. and great sheets of rain cleansed the earth. The heavens send rains to wash away the footprints of special people once they cross the great divide, and we lost an unforgettable man around 1 a.m. Samuel Steven Morton, a “renaissance man,” said his loving wife, Myra, left us.

Sam, as we knew him, was a man of many talents and he touched all who crossed his path. If you called this man your friend, you were blessed mightily. If you needed a good laugh to banish worries, you had no worries in the presence of this gentle giant who once was a professional wrestler and ballet dancer.

Wife Myra is right. He was a renaissance man. Consider the paths life took Sam Morton down … sheriff’s deputy, public relations writer at USC’s Medical School, corporate communications writer at Policy Management Systems Corporation where he won a Best of Show Addy in 1999 for the annual report and again in 2005 for the USC School of Medicine annual report. Add the roles of freelance writer, novelist, father, and husband … the list goes on as you will see and includes surprising achievements. Awards are nice but being remembered for all the right things is better.

We all will remember Sam forever. Sam was one of those people who enter a room and immediately brighten it. He was a people person and people loved to be in his presence. He filled a room with energy. To get right down to the point: he was fun to be around. And he had the soul of an artist. If Sam loved anything even remotely approaching his great love for his wife and two children, it was his love for the written word. Words brought Sam and me together, fastening us as glue binds a book, forever friends.

“I want to write,” said this burly, beaming fellow as he took his seat in a writing workshop I held at Midlands Technical College’s Harbison Campus many years ago. And write he did. A 1985 graduate of the Citadel, he earned a BA in English there and a Masters in English from James Madison University. He put them to good use. He wrote four novels and co-authored six anthologies.

He often told others in my presence that I was his mentor and when he did pride surged through me like wind off a white-capping lake, but I did nothing special. Writers are born, not made, and Sam Morton came into this life in Rock Hill April 29, 1963 with “the gift.” He wrote magazine features and brought his brand of word magic to all things he touched. Wit and zest. That’s what Sam brought to any piece of writing. Consider this excerpt from his bio. “His past occupations include a 12-year stint as a robbery/homicide detective for the Richland County Sheriff’s Department in Columbia, SC, a ten-year career as a professional wrestler, and one long week as the blade changer on the potato cutting machine at the Frito Lay plant in Charlotte, NC.” One long week … see what I mean? We feel his pain.

“Sunshine,” Sam’s personal blog, embraced those things dear to him. In his own words, “Sunshine contains reflections on the things I know best: writing, wrestling, policing, and life in general with a wife, two kids, and a dog.”

Sam was a family man, pre-deceased by his parents, Harry Morton and Dorothy Morton. He married Myra Frailey Morton November 29, 1986, and they have two beautiful children, Samuel Alexander “Alexey” and Sasha Nicholayvna “Nikki.” He has a brother, Michael R. Morton, and sister, Cathy M. Dawkins. He left behind a sister-in-law, Marnie, and two brothers-in-law, David Frailey and Dean Frailey. To them and to all his friends, Sam was a gentle giant beloved by many. A big old’ cuddly teddy bear said a friend and one-time colleague.

More Renaissance man documentation. He took great pride in being a “Dance Dad” at Timmerman School. He performed as King Neptune in The Little Mermaid. Daughter Nikki was “the apple of his eye” and Alexey “the pride of his heart.” He loved Myra, his wife, and had known her since high school. And then the years began to accumulate bringing joys and, in time, health issues.

Early April 1 Sam’s broken heart broke hearts across the land. His friends had watched his courageous battle against diabetes and heart disease for twelve years and had seen him prevail every time despite the gravest of situations. Sammy was the comeback kid, always overcoming the odds to cling to this precious thing we call life. He spoiled us with his determination. We had come to expect him to overcome anything, but now he has taken leave of us and we are staggered by his death.

South Carolina keeps losing writers. I get the feeling God is setting up a South Carolina writer’s group up there. I see Sam sitting alongside Pat Conroy, his friend and fellow Citadel graduate, and no doubt talking with the columnist, the late Ken Burger, whose service last fall was held ironically at the Citadel’s Summerall Chapel. Imagine what things this writer’s group will write.

You, the reader, taking in these words, I don’t know if you knew Sam like I did, but the following words come to mind. Colleague, co-author, comedian, Citadel man, caring, compassionate, charmer, and clever. All Cs it so happens. But you can be sure that when it came to his life and the way he lived it, he scored all As. He was a gentleman and a scholar.

And musician. Myra says he played the bass drum in the Citadel band. “He was easily spotted because he was the tallest fellow in the band.” He stood tall in other ways, too, like the way we judge character and a person’s appetite for life itself. No, you didn’t have to look for Samuel Steven Morton.

He must have made a million friends and no matter where he went, he ran into a friend. Just about everybody knew this man who could take down a bad guy wrestler, as the Patriot, and perform a comedic big jump as a ballet dancer for his kids. He lived life to the fullest.

We know he hated to let go. Oh how we will miss this man who came out of the Upstate. We all fell in love with him and his ways.

When many a lesser man would have thrown in the towel, you fought the good battle, my friend. Rest in peace dear beloved Sam, mighty warrior. We’ll not see the likes of you again. The writer, James Salter, wrote, “Life passes into pages if it passes into anything.” Sam, you left us a family and pages too. You left a long wake and much for us to remember and treasure. Each of us is better for having known you.

—Written by Tom Poland per Sam Morton’s wishes

Wild Horses

When I hear some determined soul say “wild horses couldn’t pull me away” thoughts race through my mind. First, I think of Muscle Shoals, Alabama. You’d think it’d be Mussel Shoals as mussels and waterways go together, but no, it’s Muscle Shoals. Why do I think of Muscle Shoals? Because that’s where the Rolling Stones recorded their big hit, “Wild Horses.”

Then I think of Chuck Leavell, once with the Allman Brothers Band and now with the Rolling Stones, who once worked at Muscle Shoals as a studio musician. At the tender age of fifteen, he struck out for Muscle Shoals where he began his ascent. His path and mine crossed and so when I hear those two words, “wild horses,” I think of Chuck.

Another thought sends me back to 2010 and a hot August day when I followed men on marsh tackies. They were hunting wild hogs on stalwart horses the Spanish stranded on our Atlantic shore in the 1600s. That was when stunned English explorers, mouths agape, beheld Cherokee and Chickasaw Indians riding small, rugged horses. Abandoned by the Spaniards, feral marsh tackies sought refuge in Lowcountry marshes, where they were captured and domesticated, first by native people, then by European settlers and African slaves. Conquistadors, thank you for gifting us wild horses. Whether left behind by design or here because shipwreck sent them swimming ashore, we’re glad to have them.

Yet another notion pops into my mind, Cumberland Island. Yes, Cumberland Island where another ill-fated Kennedy, John Junior, married. This national seashore is home to wild horses and the majestic ruins of a majestic place with a majestic name, Dungeness. The list of those who built and lived on Cumberland reads like a who’s who of the famous and extraordinary. Among the names are James Oglethorpe, Nathaniel Greene, Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, father of Robert E. Lee, and Thomas M. Carnegie, brother of Andrew Carnegie. It was the Carnegies who built Dungeness. Fire, possibly arson, destroyed the mansion in 1959 and today its ruins send a clear and utterly undeniable message—nothing lasts forever.

When I hear the Stones’ song or when someone says, “You know up on North Carolina’s Outer Banks wild horses run free,” I get another thought. I think of an October day when the sun rained down gold as I rode a tour boat near Fernandina Beach, Florida. We cruised along green marshes and sandy shores of aforementioned Cumberland Island. Sure enough, wild horses grazed along the edge of the maritime forest.

The next day Georgia played Florida. Just before the half in an electric three minutes and change, the Dawgs put away the Gators with a three-touchdown flurry. When the game ended, wild horses couldn’t have dragged the red-and-black throng into the streets, much less the St. Johns River, that lazy river that flows north towards Georgia.

It’s funny how the mind works. Just two words, “wild horses,” take me in several directions. Rock and roll and recording studios, an assignment to cover men hunting wild hogs, ruins and the famous, and a golden Saturday when the football gods smiled on the Dawg Nation. All of it swirls together in the colorful alchemy of the mind and its wondrous capabilities. Pray tell what do “wild horses” drag into your mind?

In the late 1990s, a time that seems ancient, I touched the emperor’s hem. That is I corresponded with a writer whose words revealed a style original and mesmerizing. Somehow, I hoped, might his gift rub onto me? I first read him in Esquire before modern, less genteel ways soiled it. That was in June 1986. His story, “The Captain’s Wife,” told how he fell in love with a friend’s wife but did not pursue her. The story’s subtitle told you all you need know, “Once Upon A Time There Was Honor In Love.”

His style of writing and his life view made me want to read more. And so I found his book, Burning The Days, Recollection in 1997. I had lost my way across the Sea of Life, and his book became my compass. I took his book wherever I traveled. I read it in hotels, at my parents’ home, wherever I ended up. I bought other books of his, and the idea came to me I should get him to sign them. But how?

I contacted a writers’ organization in New York. “Ship the books to us and we’ll send them to him and he can sign them for you.” Some money was involved. I waited and waited. Then day-of-days my books came directly to me from Salter. Now I had his address. I wrote him a thank you letter, not expecting a reply, but he wrote back speaking of the difficulty of getting published. He wrote some more.

Later he sent me a beautiful card, “Blue Nude III,” a 1952 cut and pasted paper print by Henri Matisse. On its back he told me he had just come back from Chamonix, France, where he had been shooting a documentary, largely based on his novel, Solo Faces, for German TV. “Oddly enough,” he wrote, “my biggest sales are in Germany.” He mentioned two new books coming out and something called the Internet. “I’ve never looked myself up on the Internet, must be frightening.” He closed his note, saying, “Am very grateful to you—embarrassing to talk about myself. Sincerely, James Salter.”

In Burning The Days you’ll read about Hemingway, Balzac, Roman Polanski, Irwin Shaw, Leonard Bernstein, and Robert Redford. No name appears more than Phil “Casey” Colman’s, a Georgian, a fighter pilot in Korea alongside Salter. I crossed paths with Colman at a family reunion in Lincoln County, Georgia. Many pilots attended the reunion, Colman among them. He lived in Augusta. He had no idea Salter had become a writer of high merit.

Salter wrote much about Phil “Casey” Colman, who was an ace. Here’s a bit. “It was May when Colman flew what no one except him knew would be his last mission. Colman left that day. He was lighthearted and self-promoting. Day-to-day truth was probably not in him but a higher kind of integrity was, a kind not wasted on trivial matters. He had an infectious spirit. We were unalike. I adored him.”

I handed my book to Colman. “You’re in this book.”

For an hour or more he read the book. He was old and frail and would die a few years later, but I knew exactly who and where he was at the moment. He was back in Korea and his youth had returned as he held an F-100 high above the Yalu River. In Salter’s words, “He and a MIG roared across mud flats wide open, needles crossed, the MIG like a beast of legend fleeing ahead. The controls were unyielding. The ground rushed beneath him. Destiny itself, unrehearsed, shimmered before his eyes.”

Writers, well this one at least, admire writers whose talent takes them to rarified heights. For me three stand out: James Dickey, Harry Crews, and James Salter. All as different as night and day.

Salter’s alone at the top.

People admire actors, athletes, musicians, politicians even—the list goes on. Those who commit their life to the page, flaws and all, seem the most courageous, the ones most likely to send your life in an altogether new direction.

Bitters, A History In Life And Literature

Among the dusty bottles and vase stand three alcoholic potions. I bought the matador-like bottle in Madrid when I traveled by train through hard, brown Spain. Next to it stands an elegant bottle from Italy that contains a liqueur, flavor and strength unknown. A rose and word, “Roma,” are all that’s on the bottle. To its right Angostura Bitters dominates the photograph.

The seals remain intact. Dust proves these potions have yet to be tasted. Of the three, Angostura Bitters is the one I’ve most seen in literature. It dominates there as well. It’s referred to as a botanical and contains herbs, spices and extracts of grasses, roots, leaves and fruits dissolved in alcohol. It’s promoted as “ideal for balancing alcoholic drinks, cleansing the palate and facilitating digestion.”

In 1824, Dr. Johann Siegert, surgeon general for Venezuelan military leader Simón Bolívar, created Bitters from a blend of herbs and spices to cure upset stomachs. Originally called Dr. Siegert’s Aromatic Bitters, it stops heartburn in its tracks, for me at least, but that’s not why I like it. I like it because of its place in literature.

It’s no secret that Hemingway enjoyed a drink or two, and among his favorite additives was Bitters. He liked Angostura Bitters in his gin and tonic, a fine summer drink. Among his favorite drinks when voyaging on his boat, Pilar, was Vermouth Panache, a blend of sweet and dry vermouth with Angostura Bitters. I’ve never tried it and doubt I will but some people will drive you to drink most anything. Hemingway supposedly said, “I drink to make other people more interesting.” Amen to that in this era of clones and drones glued to phones. There’s no conversing with them.

Hemingway concocted a drink he called “Death in the Stream.” He described it as “reviving and refreshing.” Amen to that as well. The drink appears in his posthumous Islands in the Stream while the main character, Thomas Hudson, is out deep-sea fishing. Excerpt—“Where Thomas Hudson lay on the mattress his head was in the shade cast by the platform at the forward end of the flying bridge where the controls were and when Eddy came aft with the tall cold drink made of gin, lime juice, green coconut water, and chipped ice with just enough Angostura bitters to give it a rusty, rose color, he held the drink in the shadow so the ice would not melt while he looked out over the sea.”

You feel like you’re there in the Gulf Stream, don’t you.

Angostura Bitters. Red like varnish, In Islands in the Stream, Hemingway also wrote, “Hudson feels the sharpness of the lime, the aromatic varnishy taste of the Angostura and the gin stiffening the lightness of the ice-cold coconut water.” I read that a bar in Seattle used 45 cases of it to varnish their wood.

It’s essential to the old Fashioned cocktail. The recipe for Angostura Bitters is a closely guarded secret. Its bright yellow cap is a trademark, but what sets apart a bottle of Angostura bitters is the over-sized label. Legend holds that when Siegert’s sons took over the business, they entered the old man’s Bitters in a competition to gain exposure. In the rush to ready Bitters for judging, one brother procured the bottles, while another had labels printed. Somewhere along the line they had a Cool Hand Luke “failure to communicate.” The labels were too big. I suppose you could say the bottles were too small. With time short, they had no choice but to stick the big labels onto small bottles. Angostura Bitters lost the competition, but a judge thought the labels set the product apart from others. Time validates his opinion.

Angostura Bitters, offered by the House of Angostura in Trinidad and Tobago and an indelible part of Hemingway lore.

Time, The Silent Thief

Growing up I could hear the tick of my church’s old Regulator wall clock. I can’t hear it today, but my hearing’s good. All that keeping of time must have silenced the Regulator’s tick and that’s appropriate. Time is fleeting in a silent unnoticed way.

I got caught up in the race and somewhere between 1996 and 2015 time stole not nineteen years but my life. One day it struck me that my daughters were grown. One day it hit me how many people I knew were dead. One day I realized others had gone into shells that swallowed their lives entire. I looked back on the jobs I’d held and how important they were but in the end they amounted to nothing. We waste a lot of time worrying when we should be remembering.

I look a lot now at what was and I do what many will think is a strange thing. On a regular basis I drive up Georgia Highway 79 and park and lean on a steel gate and stare at mom’s old homeplace. All a stranger will see is grass, trees, and an old store converted to a hunting camp. Not me. I see family. Meals. Games with cousins. Cold winter nights around a wood stove. Sinking deep into a cold feather bed. Drawing a bucket of water up from a well. A smokehouse. Penny candy. Outhouse. Crab apples. Bamboo peashooters. Arrowheads, Indian pennies, and more. Come with me one day and I’ll tell you a whole lot more about all I see in that patch of grass and weeds.

Oh. Well, that’s okay. I knew you wouldn’t have the time to join me.

Time. The New Oxford American Dictionary defines time as the “indefinite continued progress of existence and events in the past, present, and future regarded as a whole.” I define it as the stuff memories are made from. However you define it, time always seems to be in short supply but that doesn’t stop people from spending a lot of time writing about time.

In his epic poem, “Looking For The Buckhead Boys,” James Dickey gives us these lines after learning many years later that his old high school teammates are dead from heart attacks, war, and one’s paralyzed, one’s in jail, and others maligned in other ways by the clock. He remembers they lived and writes there are “sunlit pictures in the Book of the Dead to prove it: the 1939 North Fulton High School Annual. O the Book/Of the Dead, and the dead, bright sun on the page/Where the team stands ready to explode/In all directions with Time.”

Explode in all directions is right. People move never to be heard from again. Where, I wonder, is Benjamin Bradford? Where is Jean Gassaway? Where did Tommy Kennedy go? I know where Eddie, Mike, Dawkins, Janis, Sammy, and Peggy are. Gone. Gone forever. Time is fleeting and ruthless.

In “Time,” Pink Floyd gives us this line: “Ticking away the moments that make up a dull day” and this one, “Every year is getting shorter, never seem to find the time.” It’s true. A dull day seems far longer than a day spent adventuring. And it’s true that each year burns up faster than the one before.

Can you hear time? Yes, a newborn baby cries. A young boy’s voice begins to change. Brakes lock and tires squeal just before that awful sound. A siren screams down a highway. A bell tolls in the distance.

Can you see time? Sure. You see it as a tombstone. An abandoned home. A wooden cross in a highway curve. A clear-cut forest. A hearse. A wheelchair ramp.

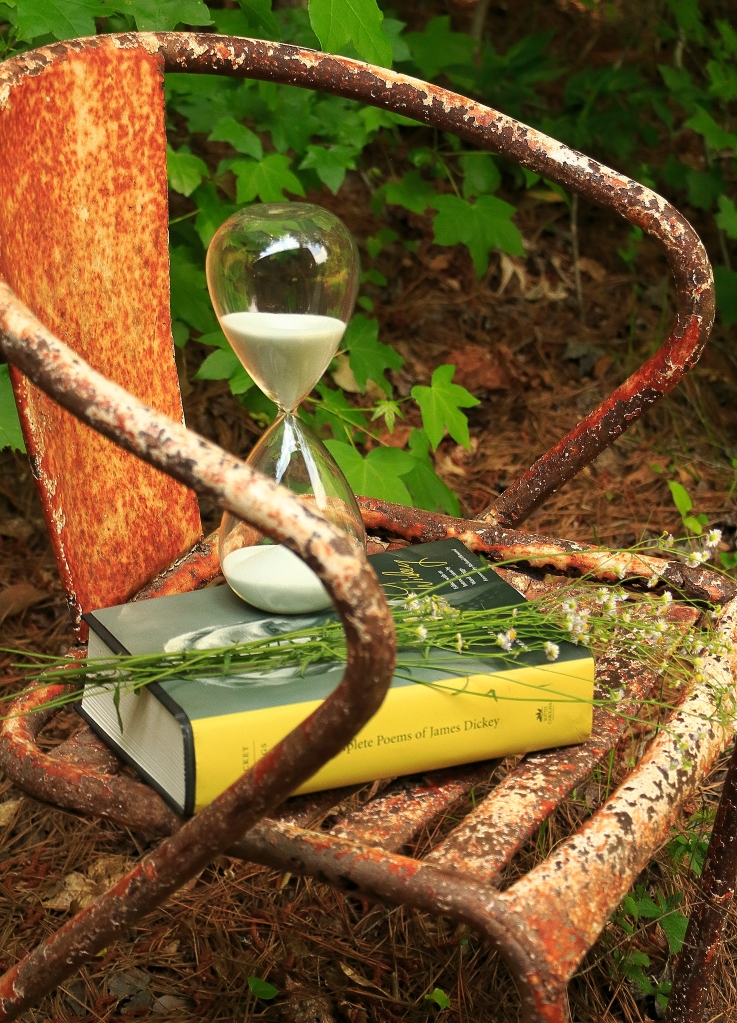

I see it as an old chair no one sits in anymore. Covered in rust with a bent leg it nonetheless possesses beauty and it’s a fine place to set a favorite book, dried flowers, and hourglass to signify the passing of time. Seems an old soap opera used to open with the saying, “Like sands through an hourglass, these are the days of our lives.”

Time. It’s the most important thing we spend. How do you spend it?

Road Side Stands

Two words say it all. “Delicious simplicity.” No register. Cash and carry. Paper bags to hold jewels polished by the farmer’s hands. A friendly face. Produce that glitters like some pirate’s chest overrun with rubies, emeralds, sapphires, citrine, and gold. From Mother Earth, as all gems are.

The roadside stand. May it never make its last stand. It might be two-by-fours cobbled together with a tin roof. It might be the tailgate of a pickup truck. It might be the overhang of an old store like this one.

Whatever its form, nothing warms my heart like a roadside stand. The steering wheel wakes up and takes control. In I pull. I buy tomatoes. Peaches. A watermelon sounds good. Crooked neck squash? I’ll grill ’em with onions. Cukes? They’ll go with the maters and onions in my salad.

Whatever its form, nothing warms my heart like a roadside stand. The steering wheel wakes up and takes control. In I pull. I buy tomatoes. Peaches. A watermelon sounds good. Crooked neck squash? I’ll grill ’em with onions. Cukes? They’ll go with the maters and onions in my salad.

My off-the-grid wanderings cross paths with roadside stands throughout the year. What freshness they hold, but to deliver the goods they must be patient. In winter, they stand empty and stark. Wood frames pale like bleached bones. Abandoned and alone. Early spring, you’ll see folks sprucing up things, getting ready for business. Summer transforms stands blanched by winter and suddenly they radiate color, energy, and the wood seems renewed as if peach, watermelon, and tomato juice soaked in by some supernatural osmosis. Fall brings scuppernongs, pumpkins, and jars of honey, which hold liquefied sun.

My off-the-grid wanderings cross paths with roadside stands throughout the year. What freshness they hold, but to deliver the goods they must be patient. In winter, they stand empty and stark. Wood frames pale like bleached bones. Abandoned and alone. Early spring, you’ll see folks sprucing up things, getting ready for business. Summer transforms stands blanched by winter and suddenly they radiate color, energy, and the wood seems renewed as if peach, watermelon, and tomato juice soaked in by some supernatural osmosis. Fall brings scuppernongs, pumpkins, and jars of honey, which hold liquefied sun.

Now I know plenty of people are content to get their produce at the big stores, but they miss a treat. When you walk up to a roadside stand you see produce bathed in the very sunlight that nurtured it. In a big store you see it laid out in rows beneath fluorescent light. Plasticized. What a drag.

Now I know plenty of people are content to get their produce at the big stores, but they miss a treat. When you walk up to a roadside stand you see produce bathed in the very sunlight that nurtured it. In a big store you see it laid out in rows beneath fluorescent light. Plasticized. What a drag.

Progress changed things for some unlucky souls. As many became more citified, as more kids grew up far from farms, voila, fruit and vegetables magically appear. Yep, a lot of people lost touch with what it takes to grow things. What’s behind split-oak baskets of peaches? Hard work, but how the work delights us.

Now don’t be surprised, maybe shocked is the word, if you come across an untended roadside stand. What? Relax. The honor system is alive and well in farm country. Heroes of the soil trust you. Just bag your tomatoes and drop your money in the jar.

Roadside stands grow beautiful memories too. On US 1 in Lexington County, South Carolina, a tractor sits next to a stand chock full of Mother Earth’s jewels. My mind transforms that tractor into the mule that dragged a plow across granddad’s field that grew light green watermelons run over with dark green, zigzagged stripes. Hey, put one in the cooler … Ok it’s icy now. Plunge a butcher knife in. Slice. Here the rift crackle like lightning as you split the melon. The red meat glows, and up drifts a sweet fragrance. Salt please. We eat it on the spot, and saccharine juice dribbles everywhere. Summertime and the living is easy.

Roadside stands grow beautiful memories too. On US 1 in Lexington County, South Carolina, a tractor sits next to a stand chock full of Mother Earth’s jewels. My mind transforms that tractor into the mule that dragged a plow across granddad’s field that grew light green watermelons run over with dark green, zigzagged stripes. Hey, put one in the cooler … Ok it’s icy now. Plunge a butcher knife in. Slice. Here the rift crackle like lightning as you split the melon. The red meat glows, and up drifts a sweet fragrance. Salt please. We eat it on the spot, and saccharine juice dribbles everywhere. Summertime and the living is easy.

Farm to table is a lovely thing, and to me a roadside stand is an extension of fertile fields somewhere over the horizon. Unless you grow your own maters and such, it’s as close to farming as you’ll get. At a roadside stand you won’t warm your hands in sun-baked dirt, and you won’t lean over to pluck some jewel from a furrow nor stretch for a limb. You will, however, satisfy that desire to grow things that’s hardwired into our DNA.

Farm to table is a lovely thing, and to me a roadside stand is an extension of fertile fields somewhere over the horizon. Unless you grow your own maters and such, it’s as close to farming as you’ll get. At a roadside stand you won’t warm your hands in sun-baked dirt, and you won’t lean over to pluck some jewel from a furrow nor stretch for a limb. You will, however, satisfy that desire to grow things that’s hardwired into our DNA.

I was telling a woman about the roadside stand you see here. She described an old screen-wire produce stand she had seen of late and then she paused so long I just knew the call had dropped. Then, “I never met a roadside stand I didn’t like.”

Neither have I.

When Dead Chickens Fly

Get Out Of Dodge

I’ve seen a dead chicken fly. I flew too.

While in graduate school at the University of Georgia, I worked as a ticket agent for Southeastern Stages, and it was my best job ever. The camaraderie and joy have yet to be surpassed. Pranksters, we agents played jokes on one another and enjoyed good clean fun … most of the time.

Saturdays, two of us would drive to Church’s Chicken and bring back fried chicken for the gang. With apologies to the Colonel, it was finger-licking good. My chicken finger-licking days, however, would give way to chicken-dodging days for one’s destiny can change overnight.

Near the end of my master’s studies at the University of Georgia, my department chairman summoned me. “I’m going to give you 10 hours’ credit for teaching six months at a college in Columbia, South Carolina.”

Before I could say George W. Church I was in Gamecock Country. Six months? How about four years. Then I took a position writing about nature. About that time, I got remanded to the correctional institution of marriage. When you are young, you are not foolish. You are terminally foolish, but fried chicken offers salvation. Thanks to Church’s chicken I’d pull off a jailbreak and make my way into writing where each day is good, none of this better or worse nonsense.

I never like being married. Made me feel like half a person, in prison no less. Like my growth was stunted. Like a serf or vassal. Formal education teaches us much but life teaches us more, a lot more. I watched others marry and divorce. Saw deception and disillusion. Witnessed the struggles, the draining of personality, the strain of splitting assets, the breaking of hearts, the breaking of families. Those who settled in? I noticed how veteran married couples seemed, well, I’ll just say it. Boring as hell. No spark. No zest. They don’t even talk in restaurants. Just sit and eat and eat and sit.

Marriage? A big thumbs down. Outside of family, I know of few good marriages and I try not to hang out with people with their ankles chained together. The borderless country of Matrimony? I threw my passport in a ditch. Writing gave me a companion for life, not for better or worse, but better, always.

Suffering gives a writer empathy they say. Makes a writer sensitive and thus a better writer … they say. Well, I say I ought to be the world’s best writer. I sense all right. Sense when to rhyme words. An alluring responsible woman? “Beautiful and dutiful.” A crotchety old man, “Crude and lewd.” When some minion says “my Mrs. the wife,” I sense strife, knife, as in the back, and life, as in a prison sentence. When some numbskull says “me and the spouse,” douse, as in ruining joy, grouse, not the game bird, and house, as in arrest, come to mind. “Matrimony?” Acrimony, alimony, testimony, baloney, and phony. But like so many other hapless young men, I fell victim to vows. I wed, which rhymes with dead, bled, and dread. I myself tied the knot in a hangman’s noose. Yep, I signed up to become a beat-down hangdog daddy pushing a grocery cart behind a wide four-letter word that rhymes with strife.

Things went downhill in a hurry. I should have never left my bus-station buddies but thank God my craving for Church’s Chicken followed me to Carolina. And that, my friend, brings me to the day a dead chicken sprang me out of jail.

My wife ordered me, ol’ hangdog daddy, to the grocery store solo, which meant for once I could appreciate the pretty women sure to be shopping. (No mean stares or pinches.) My instructions were to procure bread, a gallon of milk, and Dr. Scholl’s heavy-duty corn remover. Gathering up my courage, I squeezed out eight life-changing words. “Do you want some Church’s chicken for dinner?”

Yes!

Off I go to Big Star, my mind on chicken. I got milk. Got bread. Ah, a six-pack of Pearl beer would go well with hot fried chicken. Out the door I went. I picked up a box of chicken and headed home.

I placed the bread, milk, and beer on the counter. The warden comes to inventory things. “Where’s the corn remover?” (Corns must hurt like hell. Don’t know. I never crammed a wedge of cheese into a matchbox.)

“Ah, crap, I’ll go back.”

“Well, you got beer, didn’t you. You got beer! Didn’t you! Didn’t you!” Her nostrils flared, her face reddened and twisted into a murderous visage, and I paled, knowing at once why men on safari fear cape buffaloes. In a spleen-splitting nanosecond of rage, she catapulted my box of Church’s fried chicken at my face. At my face.

Folks, you don’t forget moments when time stands still. Moments when nerve endings crackle and fire up the instinct for survival. Like some rocket-tracking camera, my eyes locked onto that spinning blue-and-white box hurdling at me. Though it was approaching escape velocity I could read “Just Like Home” and “Dig In.” Dig in hell. That’s when I ducked.

I looked up to see a breast fly out, then a leg, the other leg, then the other breast, all glistening in battered golden-fried-chicken splendor. The wings cut loose and lo and behold a jalapeno pepper shot free. A headless chicken trailed by a fluffy brown biscuit zoomed over, like one of those stadium flyovers. In horror I turned to see this featherless flight splat against fake pine paneling. Rivers of grease dribbled down the wood and all that glorious chicken hit the floor. Kersplat. Chicken carnage. In one of those miracles science can’t fathom, the jalapeno pepper landed square on the biscuit.

“Well, damn, look at that,” I said.

Then to myself, “I am outta here faster than a bat out of Hell.” And I was.

It took a day or so to flee for good, but soon I rented an apartment, took my dog, pick-up truck, and TV with me and commenced to sleep on a brand new sofa bed from Rhodes Furniture. I had nothing but I had everything.

My first night in my new home? You guessed it. I enjoyed a fine meal of Church’s liberating fried chicken, washed down by Pearl beer.

And that flying wall-splattering dead chicken? Well, I don’t know if the soon-to-be-ex chowed or not. Probably. Carnivores eat their kills. But let me tell you, it was the best fried chicken I never ate. It gave this old hangdog daddy his life back, and for that I thank you, George W. Church. I thank you to this day. I thank you every day. God bless you and your jalapeno peppers. Like them, I too knew just where to land—in a place all my own, a place called bachelorhood.

The jumping off place for Cape Romain.

For The Birds

Note: This essay appears in State of the Heart, South Carolina Writers on the Places They Love (Vol. 1), Aida Rogers, University of South Carolina Press.

For three summers running in the 1960s, I spent two weeks at my aunt’s home in Summerville. Daily trips to Folly Beach made my heart beat wildly. All that openness, sun, sea, and stretches of beach created a horizon like no other. I could see for miles.

When I went back home to eastern Georgia’s forests and hills, the world closed in on me, and a longing for salt, sand, and spray consumed me. The surf kept calling in the whelk shell I held to my ear. Nothing’s worse than growing up landlocked once you’ve had a taste of the sea.

Rural outposts grow big dreams in country boys and my dream was to live on the coast. Fate, however, had something else in mind – something beyond the coast –beautiful islands in a beautiful refuge called Cape Romain.

In 1978, I applied for a job as a scriptwriter and cinematographer for natural history films. Three finalists had to write a 15-minute script on the eastern brown pelican. My script, The Magnificent Pelican, cryptic wordplay involving my initials TMP, landed me the job, and for a deliciously brief time, I worked on the wild islands of Cape Romain Wildlife Refuge.

By Day

Even a sorry photographer knows the best light is at dawn. Up at 2 a.m., I would race the sun to the coast, the light falling in my wake on haunted, green swamps and oaks dripping with Spanish moss. The stars told me I was moving deeper into the land of blackwater rivers and white sands, so deep my journey would take me to the jumping-off place, a landing at McClellanville.

McClellanvile, the quaint fishing village that welcomed Hugo ashore in 1989, sits just off Highway 17. Like a sea breeze, 17 blows through a land of tradition and awe. Where else do you see black women weaving sweetgrass baskets along green highway shoulders, come across a majestic name like Awendaw, or discover a wild refuge?

My first crossing was one to remember. In predawn darkness, we put out in a Boston Whaler manned by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service boatman Herbert Manigault. The Whaler’s engine hummed as we made our way through the estuary and breakwater to one of the last wild islands, Bull Island. About 300 yards from the marshy side, Herbert killed the engine. The unceasing sound of 10,000 Dewalt drills piercing steel crossed the water – mosquitoes by the millions.

I didn’t care. I felt as if I were about to step onto the shores of Africa. And I felt this way for three summers in Cape Romain, a refuge that wraps barrier islands and salt marsh habitats around twenty-two miles of Atlantic coast. The refuge holds 35,267 acres of beach and sand dunes, salt marsh, maritime forests, tidal creeks, fresh and brackish water impoundments and 31,000 acres of open water. Nature rules. It is an ideal place to film wildlife for a simple reason: Man has yet to ruin it.